The best tales get told again and again, and Clive’s short story, The Forbidden, filmed as Candyman and its movie sequels, falls squarely in that slot.

Originally published in 1985 in Volume Five of the Books of Blood, Clive was inspired by cautionary tales told to him as a child by his grandmother.

Marrying common elements and fears - the hook-handed man, castration, the uncatchable killer and urban brutality - the story explores not only the narrative of an urban myth but the very nature of mythology, playing on the fame of a whispered myth as it spreads:

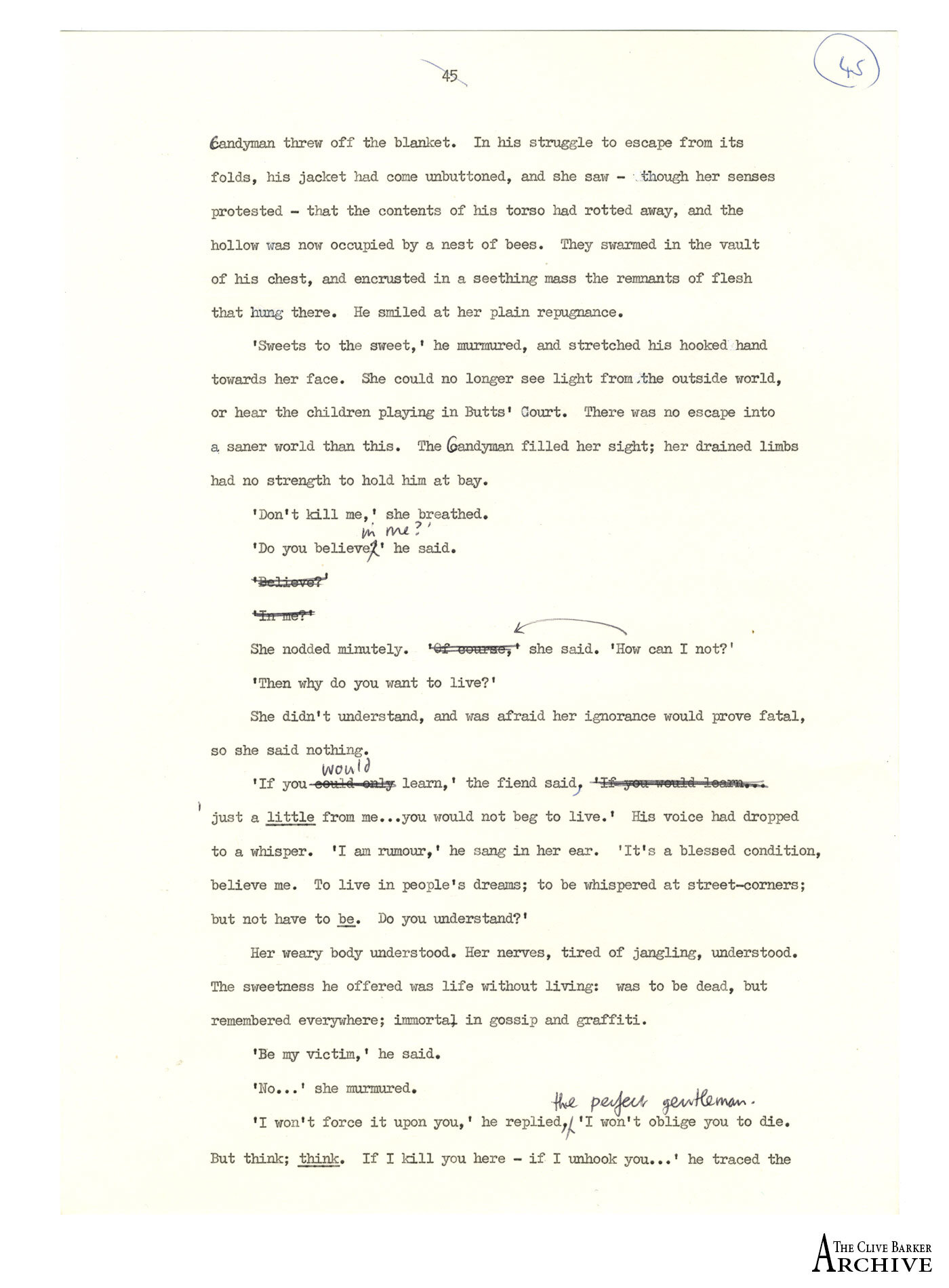

‘I am rumour,’ he sang in her ear. ‘It’s a blessed condition, believe me. To live in people’s dreams; to be whispered at street corners, but not have to be.’

“I was writing about the experience of horror,” says Clive. “This was about why we write those tales, why we hear those tales. The story was about story itself.”

The character of the Candyman draws upon a motif Clive had long been developing since writing his 1973 play, Hunters in the Snow - that of the calmly spoken gentleman-villain - who seduces Helen with the poetry of Shakespeare and the measured rhythms of a lover. Hellraiser’s Pinhead would later share some of these characteristics and be all the more terrifying for it.

“I use a quote from Hamlet in the story: Sweets to the sweet,” he notes. The earlier origin of the quote is Biblical:

Judges 14: 14: “And he said unto them, Out of the eater came forth meat, and out of the strong came forth sweetness.”

“In England, we have golden syrup. The makers of this syrup put on their can a picture of the partially rotted corpse of a lion with bees flying around it, and the Biblical quote…”

The makers of the golden syrup were Tate and Lyle. Clive had named his heroine Helen Buchanan (but Bernard Rose later renamed her Helen Lyle) and the bees and the sweetness coalesced into the story elements.

As Clive notes today, the figure of the Candyman in The Forbidden wears a motley, his appearance is multi-coloured, standing for every kind of ‘other’ - making his universal story adaptable to resonate widely with all who are outsiders or marginalised.

He was bright to the point of gaudiness: his flesh a waxy yellow, his thin lips pale blue, his wild eyes glittering as if their irises were set with rubies. His jacket was a patchwork, his trousers the same. He looked, she thought, almost ridiculous, with his blood-stained motley, and the hint of rouge on his jaundiced cheeks…

And she was almost enchanted. By his voice, by his colours, by the buzz from his body.

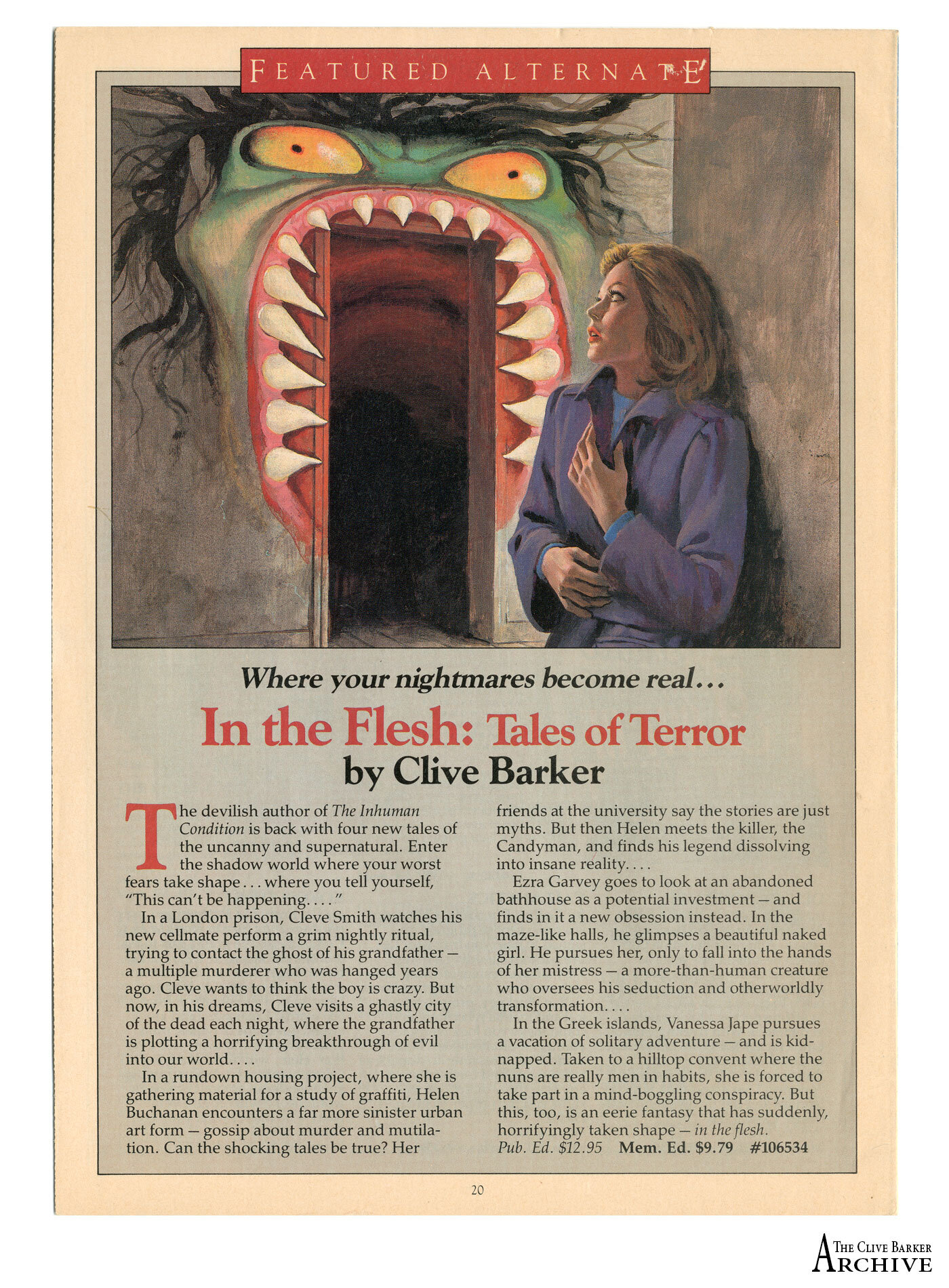

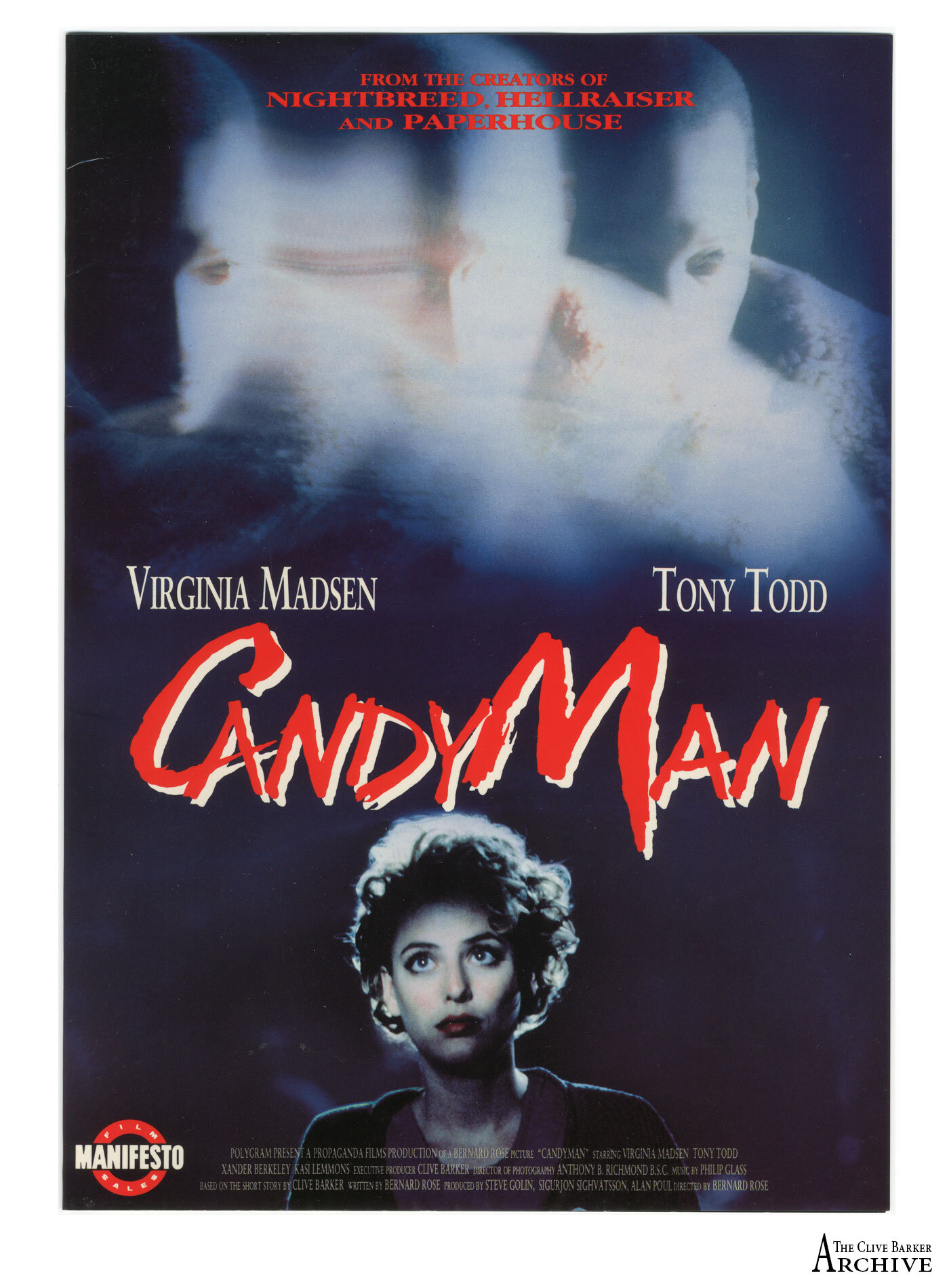

The short story is set in Clive’s hometown, Liverpool, and the re-location to Chicago can be credited to Bernard Rose, as he and Clive discussed its adaptation for the cinema. Bernard also added the Bloody Mary element of invoking the titular presence by repeating his name in a mirror and the Candyman, played by Tony Todd, reflected the racial and urban setting of Chicago’s Cabrini Green estate.

[Candyman] was Bernard Rose's baby from the beginning. We shared an agent at CAA and I'd enjoyed Paperhouse - I thought it was tremendous, a smashing picture. Adam [Krentzman] said, "you know, Bernard really likes your short stories and there are two or three he's interested in and would like to get going...”

Anyway, his favourite story was The Forbidden, because he wanted to deal with the social stuff. He liked the idea of taking a horror story with some social undertones and making a movie of it. This was while I was still living in London, and we sat down several times and talked it through. We agreed that it needed to be relocated to the United States because it was American money and they weren't going to be interested in a story set in Liverpool. But the Cabrini Green setting I think worked perfectly well. He took the thematic material in the story and expanded it and turned it into something that was very much his own. I watched over the thing and worked with him and story-conferenced with him and did all those things, but at the end of the day it's Bernard's movie and I think he did a tremendous piece of work.

As Clive noted on the soundtrack liner notes, Philip Glass’ work had an extraordinary impact on the movie:

Philip elevates horror and suspense to an epic plateau. Moving between the gentle toy piano touches of a child's grim fairy tale and the sinister pipe organ of the most fearsome of fire and brimstone sermons, Philip Glass has found a way to evoke the web of the collective fears woven across the span of a human lifetime and lay it like a shroud across an hour and a half of our lives. To this very day, this music still sends chills down my spine.

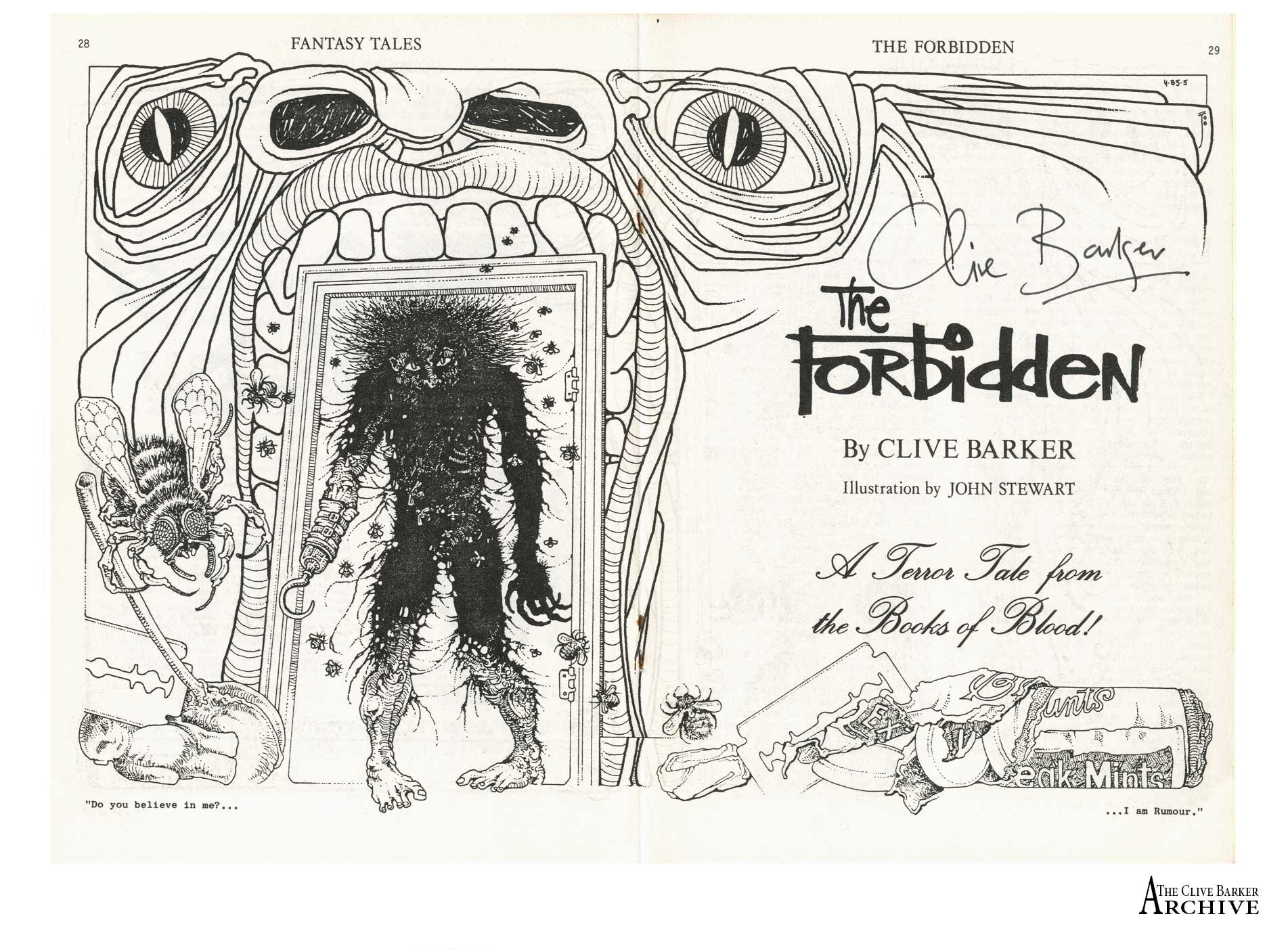

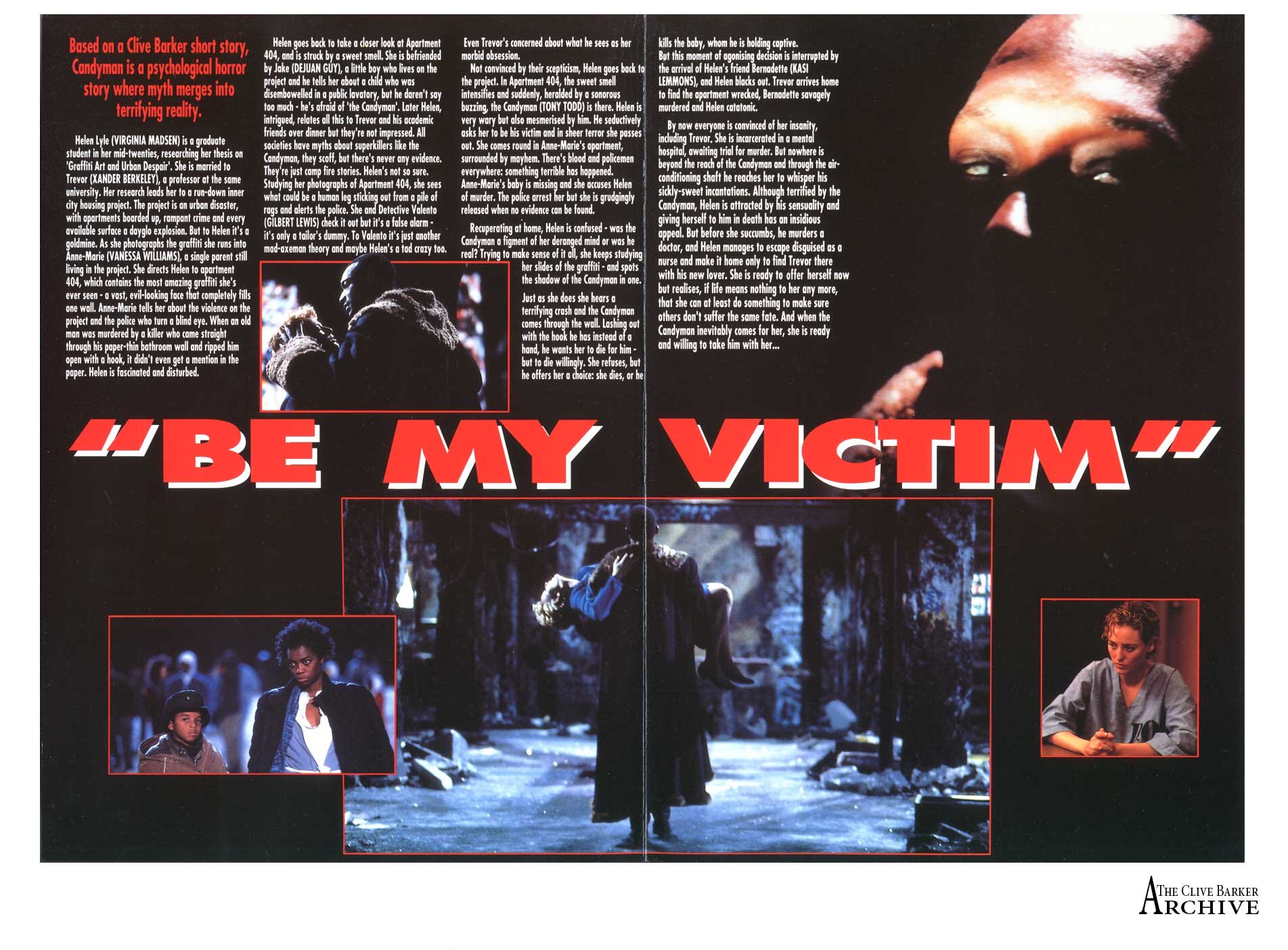

Shown below and in the Archive Gallery are two pages from Clive’s handwritten draft, this same sequence in Clive’s final hand-amended typescript for the Books of Blood, the artwork (by John Stewart) that accompanies The Forbidden’s first stand-alone publication in Fantasy Tales in the summer of 1985, a 1987 Literary Guild advert for the US publication of Volume Five as In The Flesh, a Manifesto Film Sales brochure from 1992, the cover and title page of Bernard Rose’s film script, signed by Virginia Madsen, and the review and listing of Candyman’s screening at the 1992 London Film Festival.